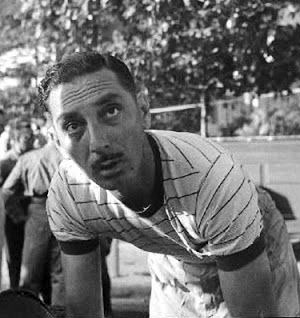

Luigi Emilio Rodolfo Bertetti Bianco, better known as Gino Bianco (22 July, 1916 – 8 May, 1984) was a racing driver from Brazil. Born in Milan, Italy, he emigrated to Brazil as a child and started racing there.

He raced a Maserati A6GCM for the Escuderia Bandeirantes team and took part in four Formula One World Championship Grands Prix, with a best result of 18th at the 1952 British Grand Prix. Bianco later raced in hillclimbs and died in Rio de Janeiro, aged 67, after suffering from breathing problems. Info from Wiki

Info Hans Hulsebos

Escuderia Bandeirantes owner Eitel Cantoni acquired a couple of Maserati A6GCMs in 1952. Both Maseratis were available first time at the British GP with Cantoni and Brazilian “Gino Bianco” making their championship debuts. But the Uruguayan retired after just one lap and mechanical failure also saw him sidelined in Germany. The team expanded to three cars for the GP du Comminges at St Gaudens but Cantoni and his team-mates all failed to finish – the story of the team’s season so far.

Cantoni made his final GP start at Monza and finished a distant 11th when five laps off the pace. Seventh in a non-championship race at Modena was his best result of the season and ninth at Avus his last race of his only European campaign.

He returned to Uruguay at the end of the year and did not race again.

![]() Bio from Reddit – Part 1: Unusually Unreliable Italian Immigrant

Bio from Reddit – Part 1: Unusually Unreliable Italian Immigrant

Gino Bianco was not Brazilian born. He wasn’t even a naturalized citizen of Brazil throughout his career, even though he always raced under the Brazilian flag. Heck, his real name wasn’t even Gino Bianco.

He was born either Luigi Emilio Rodolfo Bertetti Bianco or Luigi Bertetti Bianco, depending on which source you choose to believe, in Turin, Italy on July 22nd, 1916. His childhood in Italy must have been amazing, given how his father was a worker in a candy shop in Turin at the time. By age 12, though, Bianco’s family packed up and emigrated to Rio de Janiero, one of the many Italian families to do so at the time. Bianco caught the racing bug a few years later, where he reportedly was a spectator at the first Rio de Janeiro Grand Prix at the Gavea circuit

Though young Luigi might have been hooked on racing, being 17 was far too young for one to enter a race at the time, especially in a country like Brazil where motor racing wasn’t exactly the biggest thing going on at the time. Still, Bianco managed to get involved in the auto industry in some fashion, managing to get a job at a workshop that was literally next to Copacabana beach.

His first taste of auto racing would come in 1938, when Bianco’s garage owner, Mauricio Dantas, entered the event at Gavea for himself. However, for some reason or another, Dantas was unable to participate. And so, he nominated Bianco, then entered under his birth name Luigi, as his substitute for the race. For his first time out, Bianco didn’t embarrass himself. Indeed, on a circuit that looked like a tighter version of Macau, in a race where only eighteen out of 45 entrants could qualify, Bianco placed his car eighth on the grid. However, his race didn’t even last one lap, getting caught in a first-lap incident.

In fact, for a good eight years, that incident pretty much summed up Gino Bianco’s racing career. Up until 1940, Bianco only raced at the annual race at Gavea and the very first race at Interlagos. He failed to finish each and every time, even flipping in the 1940 race at Gavea. Even though racing was truncated during World War II in Brazil, as you’d expect, there was still the occasional race here and there. And, for most of them, Gino Biacno would be among the retirements. Despite all this, Gino still found time to open his own workshop at the Ipanema area, servicing not just regular customers, but plenty of potential racers as well.

Gino seemed to have a thing for hillclimb races though, being a frequent participant in the Rio-Petropolis event, winning the 1946 edition in addition to a few other podiums elsewhere. Despite his affinity for hillclimbs, Gino still raced in quite a few circuit races, and after a good eight years of middle-of-the-road results, things finally clicked for Bianco on the race track in 1947. He took part in two races at Interlagos in the beginning of 1947. He finished in third in the first event, but if it weren’t for a late splash-n-dash, Enrico Plate wouldn’t have passed him for 2nd. The second event was of much greater significance. It was the Grand Prix of Interlagos, one of the first international racing events hosted in Brazil. Two Italian stars, Achille Varzi and Luigi Villoresi, would be competing. Entering a private Maserati that he owned and had been racing for a while now, Bianco took a punt and entered the event.

In that event, Bianco managed to finish third. Okay, given how the race only had three finishes, not that impressive, but it was a minor victory for Gino. Given how he was still winning hillclimb events, it seemed like the future would be bright for Gino, but it got dark very, very quickly.

To call his 1948 season subpar would be boringly accurate. And starting off 1949, Bianco was involved in one of the craziest races in Brazilian racing history, the Belo Horizonte Grand Prix.

The Grand Prix was set on quite the stage. A circuit around 20 kilometres in length, running past an artificial lake that was the gleaming attraction in the city of Belo Horizonte, this Grand Prix was set to be a wonderful attraction to the city. An event that was set to be paired alongside those at Interlagos and Gavea as one of the premier events in Brazilian motor racing. Instead, it descended into tragedy and chaos. One the second lap, Antonio Fernandes da Silva lost control over a bridge and rolled into a ravine. His Alfa hit a few concrete support pillars and was split into three in the crash. Fernandes da Silva’s right leg had to be amputated as a result from said accident. That accident sounds huge, but it wasn’t even the biggest accident that day at Belo Horizonte. And in this second crash, Bianco was involved.

Bianco and Otacilio Rocha were having an absolutely crazy battle over third place. Heading up to the end of the fourth lap, Bianco and Rocha were still neck and neck. Heading into a very fast turn near the pits, Bianco went side by side with Rocha. Rocha lost control and mounted a kerb, headed right towards a packed spectator area.

One eyewitness saw Rocha steer the car towards a telegraph pole in front of the crowd to try and avoid running down any spectators. The collision with the post was so brutal that the pole collapsed on impact. Rocha died on the way to hospital, but his last-second decision to impact the pole meant that only one individual, a civil guard, was sent to hospital, while only a few spectators suffered minor injuries.

After that incident, the crowd started to get much closer to the track. Sources vary as to why, either because they were too rowdy and wanted a closer look, or they wanted to bring the race to a halt after those two major incidents. Whatever it was, the police chief found the situation was getting dangerous, so he put a halt to the race two laps early, with Chico Landi getting a hollow victory and Gino Bianco with an empty third place. As far as I know, there’s not been another Grand Prix at Belo Horizonte again.

After being involved in that incident with Rocha, Bianco could’ve had the need to recuperate. After an accident like that, one might think that Bianco would never be the same driver again.

But after that accident, Bianco suddenly became one of the fastest drivers in Brazil.

Part 2: Killing it on the Track, Suspected Killing Off It

After a race in Boa Vista, where Bianco finished fifth, he decided to take part in the first running of the hillclimb championship in Brazil, a four round championship with all its rounds taking place in the state of Rio de Janeiro. With hillclimb being Gino’s calling card, it seemed like a good way to revitalize his racing career after a sub-par 1948. He did more than just revitalize it.

In that four race championship in 1949, Bianco won three races and finished second in the final round. That was his first title.

In the four race championship the next year, Bianco won three races and finished second. That was his second title.

Two hillclimb championships in two years. And he would go ahead and claim this third consecutive title in 1951. Though it is unclear how many races he won in this title, a particularly interesting event occurred at the hillclimb at Canoas. That day, Bianco had already set a blistering time in his Maserati, but he didn’t feel that was enough. Borrowing Antonio Pinheiro Pires’ Talbot, he re-entered the same hillclimb event, with race officials somehow allowing him to take part. And he set a time only marginally slower than his own in the Maserati. With nobody able to beat his times, Gino Bianco finished both first and second in the same hillclimb event, just because he could.

So, Gino Bianco. The guy who couldn’t finish any race to save his life early on in his career. The guy who only had form in patches throughout his career. After 1951, he would be the guy who was unstoppable in Brazilian hillclimbing, with three national titles in a row. In 1952, Bianco was looking to transition to more circuit races. However, his season got off to a rough start because of two more deaths that he was involved in. One on-track and one… off track?

First the on-track incident. His early 1952 form was off to a rough start and it seemed that Bianco was reverting back to his woeful, pre-1947 form of constant DNFs. At the very wet race at Quinta da Boa Vista, Bianco found himself in a battle with Pinheiro Peres, the guy who lent him the Talbot in that solo 1-2 feat I mentioned earlier. Reports differ as to whether Bianco lost control on his own or if he lost control after tangling with Pinheiro Peres, but the incident cost the life of a spectator, Raul Vieira Rangel.

The second death was off track. And it wasn’t just any death. It was one of the biggest murder cases in Brazil at the time.

April 6th, 1952. Banker Afranio Arsenio Lemos was found dead in his black Citroen on top of the Sacopan hill. Robbery was ruled out early on, but all attention turned to the image of one girl that was found on Lemos’ body, an 18 year-old by the name of Marina Andrade Costa. I can judge that Brazilian newspapers in the 50’s were sensationalized, because with that picture, the murder gained incredible news coverage. And, like any news coverage that tries to employ a ‘whodunit’ strategy, they started suspecting quite a few people who could be involved. Why they killed Arsenio Lemos in his car. Why a picture of Marina Costa with him.

And, somehow, some reporters suspected that the murderer was none other than Gino Bianco.

You see, Arsenio Lemos was an avid motor-racing enthusiast, and whenever he’d want participate in hillclimb events, he’d approach Bianco for help. As one of the few high-profile names that could be linked to this case, he was an obvious target for reporters to jump on.

Turns out, when newspapers jump to conclusions before the police does, don’t trust them. Bianco never saw Arsenio Lemos that day. He was in a bar with his wife (making any romantic link with Marina near-impossible) and a few of his friends. He did see the black Citroen drive by, but didn’t think anything bad happened until he read the newspapers the next day.

As it turns out, Gino Bianco had no involvement whatsoever in ‘The Crime of the Sacopan’, one of the most famous criminal cases in Brazil at the time. This incident was pretty much a media circus at the time. Movies were made about it. 50 years after the incident, a documentary was made about it. Check it out in your spare time.

Besides, once Gino Bianco had cleared his name, he had bigger things on his mind. Come June, he wouldn’t be defending his national hillclimb title for the four-peat. Instead, he was going to race internationally. And not just any series, but the big stage.

He was going to take part in the World Driver’s Championship.

Part 3: European Experiment.

Yep, Gino Bianco was going to participate in Formula One. Though not quite Formula One. This was 1952, remember. Back then, the World Driver’s Championship, the one we know and love, was run under Formula Two rules back then. This was to try and encourage a wider variety of entrants into the World Championship as, by that point, only Ferrari were committed to building Formula 1 cars for 1952. As expected, there were indeed several entries with all sorts of constructors from all over the world, some of them constructor entrants, some privateers. One of these privateers came all the way from Brazil.

This privateer was Escuderia Bandeirantes, but who exactly was running and financing it remains a bit sketchy. The only thing that wasn’t in doubt was that Chico Landi was the main man when it came to heading operations on the track. Landi was the name for Brazilian motorsport, having won several pre-war races in Brazil and he even had a Formula 2 victory in Europe at Bari in 1948. He was also the first Brazilian entrant to a Grand Prix, though his only start in the 1951 Italian Grand Prix ended in a retirement. Still, he was leading Escuderia Bandeirantes into a full, three-car effort heading into the World Driver’s Championship, and Landi insisted that the three Maserati A6GCM’s purchased for the team be painted in the national racing colours of Brazil, yellow with green wheels.

The main issue here comes with who exactly ran the team with Landi. Some sources state that only the Uruguayan Eitel Cantoni ran the team with Landi, others state it was the effort of a full quartet of drivers: Landi, Cantoni, our man Gino Bianco, and Argentine Alberto Crespo, which seems odd given that he drove for another South American team, Enrico Plate, later that season.

If there was a mystery as to who was alongside Landi in their day-to-day operations, it was a bigger mystery as to who funded the team. Some people thought it was Chico Landi, but Landi was one of the few drivers in the fifties without bags of money behind him. His father was a farmer who died early in his life and Landi had to enter the workforce by age 11 just to keep his family afloat. Other sources again state Cantoni, but it was unclear whether he was truly involved in running the team or if he was just a driver. One definite source of funding, though, was the Brazilian Government themselves. It was hard to transport three Maserati A6GCM’s across the Atlantic to Europe, but Landi had said that they were able to get transport with the help of the state at the time. With all that sorted, Escuderia Bandeirantes were off to Europe, and Gino Bianco was in tow.

After Bandeirantes entered Philippe Etancelin as a one-off in France, where he finished eighth, both Eitel Cantoni and Gino Bianco were entered for both the British Grand Prix and the German Grand Prix. And it was fair to say that Escuderia Bandeirantes weren’t the best outfit on the grid. They qualified in a disappointing 27th and 28th and Cantoni didn’t even finish a single lap before a brake issue ended his race. Gino Bianco did manage to finish a race, as a result becoming the first Brazilian driver to finish a World Championship Grand Prix, but that result was still a lowly 18th place out of 22 starters.

At the next race in Germany, Bianco was far, far better than Cantoni in qualifying, placing 16th in a field of 34, where Cantoni was only mired in 26th, amongst the masses of German one-off entries. However, this time it would be Bianco’s turn to retire from the race without completing a lap, thanks to his engine giving up the ghost. This left Landi concerned about his team. So, for the upcoming Dutch Grand Prix, not only did he enter a local driver, Jan Flintermann, in the third, unused Maserati, but he took over as main driver for his team, leaving both Bianco and Cantoni to share one car for the race, as the rules allowed at the time.

Bianco wasn’t exactly happy with that decision, and he sure showed it. Given the task to qualify the shared car at Zandvoort, he showed up both Landi and Flintermann, qualifying three seconds faster than the pair of them. However, that spot on the grid was probably the biggest highlight in Bianco’s Grand Prix career. In the race, Bianco dropped to stone dead last by the end of lap one, and by the end of lap four he had left the race with a gearbox issue. Landi and Flintermann, in the meantime, shared one car to finish eighth. Things didn’t get better for Bianco in Italy, though at least he qualified for the race, barely beating Charles de Tornaco for the final spot on the grid. Still, if outqualifying Landi by three seconds at Zandvoort was his achievement, Landi outdid Bianco at Monza, this time beating Bianco’s time by four seconds. As Landi finished eighth and the best privateer finisher, Bianco’s engine gave up the ghost while in 14th.

With a lack of funds, that was the end of the road for Escuderia Bandeirantes in Grand Prix racing. Likewise, that would start to signal the end of Gino Bianco’s career in motor racing. He would return to Brazil to claim one more hillclimb championship, his fourth, in 1953, but reaching 38 years of age and after a hefty accident at Gavea, the same circuit where he started his career, Gino Bianco retired from motor racing. He sold his trusty Maserati, the one he used for all his domestic races and hillclimbs, and focused on running his workshop in Ipanema for both motor racing enthusiasts and regular motorists alike.

Seven years after retirement, he made one final cameo appearance as a co-driver to Marcelo Lemos, nephew of President Juscelino Kubitschek, for the 1961 500 Kilometres of Interlagos, where they finished 8th. Apart from that one outing, though, Bianco stayed away from public life until his death in 1984 from respiratory complications.

Gino Bianco may be a footnote in most Formula One history books, but in Brazil, he was a dominant hillclimb champion, a pioneer in Brazilian motorsport and the first Brazilian to ever finish a World Championship Grand Prix. Also, a possible murder suspect as a result of media speculation. But still a dominant figure in Brazilian motorsport nonetheless.